- Nutrients, foods, and diets

- Dietary adequacy and nutritional requirements

- Diet variation, quantification, and misreporting

- Food composition data and databases

- Data processing

- Introduction to subjective measures

- Estimated food diaries

- Weighed food diaries

- 24-hour dietary recalls

- Food frequency questionnaires

- Diet checklists

- Diet histories

- Technology-assisted dietary assessment

Food frequency questionnaires

Food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are designed to assess habitual diet by asking about the frequency with which food items or specific food groups are consumed over a reference period [1-3]. This method can be used to gather information on a wide range of foods or can be designed to be shorter and focus on foods rich in a specific nutrient or on a particular group of foods e.g. fruit and vegetables. Since FFQs are often designed to assess the ranking of intakes within a study population, it remains controversial whether FFQs can produce accurate estimates of absolute intakes of foods and nutrients. The outcomes measured by FFQs are described in Table D.10.1.

Table D.10.1 Dietary outcomes assessed by food frequency questionnaire.

| Dietary dimension | Possible to assess? |

|---|---|

| Energy and nutrient intake of total diet | Yes |

| Intake of specific nutrients or food | Yes |

| Infrequently consumed foods | Yes |

| Dietary pattern | Yes |

| Habitual diet | Yes |

| Within-individual comparison | Yes* |

| Between-individual comparison | Yes |

| Meal composition | Yes** |

| Frequency of eating/meal occasions | Yes |

| Eating environment | Yes** |

| Adult report of diet at younger age | Yes** |

* possible if repeated measures are collected over time.

** possible if specific questions for a diet during a specific period are included.

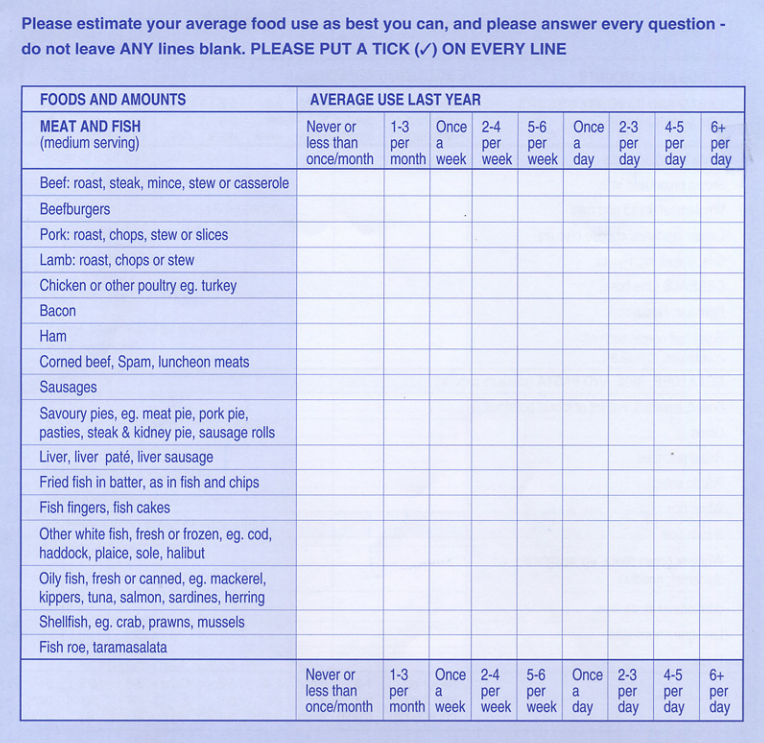

An example of an FFQ is displayed in Figure D.10.1. A FFQ can be:

- Self-administered using paper or web-based formats

- Interviewer administered through either face-to-face or telephone interview

The reference period

- The reference period usually corresponds to the previous year, in order to account for seasonal variation

- The reference period could be specified differently when recruiting certain populations or investigating certain disease outcomes or specific nutrients

The foods list

The length of the list of foods can range from about 20 to 200 items. This depends on how the FFQ is designed (see below). The foods listed should be a combination of:

- Major sources of a group of nutrients of particular interest

- Foods which contribute to the variability in intake between individuals in the population

- Foods commonly consumed in the population

Some FFQs may include supplementary questions relating to:

- Cooking methods and specific types of fat, bread, milk, and additions to foods e.g. salt

- Brand name information e.g. breakfast cereals, oils, margarine, dietary supplements, which can require considerable effort to code and analyse

- Open-ended section where respondents may record consumption of other foods not included on the food list

- Dietary behaviours e.g. dieting, meals with family members, and others in relation to research questions

- Frequency of a diet on a specific occasion (e.g. breakfast, dining outside, BBQ)

Some responses may also help to identify respondents whose diet is very unusual, for whom the FFQ may not be appropriate.

The frequency categories

- The frequency of food consumption is assessed by a multiple response grid in which respondents are asked to estimate how often a particular food or beverage was consumed

- Categories ranging from ‘never’ or ‘less than once a month’ to ‘6+ per day’ are used and participants have to choose one of these options

- The number of categories used varies from 5 to 10, but for some studies, more categories may be preferred to capture the variation in scores from a more diverse selection of foods

Use of portion sizes

Some FFQs are known as ‘semi-quantitative’, including portion size estimates. In a semi-quantitative FFQ, respondents are asked to indicate the frequency of consumption of specific quantities of foods (e.g. ½ a cup, ¾ cup etc.). By contrast, quantitative FFQs are used to ask respondents’ usual portion size based on a specified measure.

The potential contribution of questions on portion sizes is debatable for several reasons:

- The ability of the population to accurately assess portion sizes is often limited

- The variability in portion sizes in the population

- The lack of availability of current average portion size data. While some data is available, this becomes outdated very quickly

Use of a fixed portion size is not necessarily bad. If a study population is homogenous and sufficiently educated, respondents may readily calculate a frequency of food consumption given a fixed portion size. This capability of respondents is supposed to be verified in a validation study in a study population.

Figure D.10.1 Example of a food frequency questionnaire section for meat and fish.

Source: EPIC-Norfolk

FFQs are one of the most commonly used retrospective methods in nutritional epidemiology and have become a key research tool in examining the relationship between dietary intake and disease risk. For this purpose, it is more important to rank the intake of individuals relative to others in the population (e.g. high, medium, or low intake) or as quantiles (e.g. fifths of the distribution of intake) than to determine the absolute intake.

FFQs may be a particularly useful method to measure specific dietary behaviours and intakes of particular food groups (e.g. fruit and vegetables), foods not consumed on a daily or weekly basis in a given population (e.g. oily fish), or selected micronutrients present in a limited number of foods (e.g. calcium).

Due to their ease of administration and relatively low respondent burden, FFQs have been used extensively in large-scale cohort (prospective) studies such as:

- The Whitehall II study [4,5]

- The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) - for which different questionnaires were developed and validated for use in the various participating populations [6]

- The UK Women’s Cohort Study [7]

FFQs can be adapted for a particular purpose e.g. to assess calcium intake or habitual consumption of oily fish, but in many cases a comprehensive food list is used so that intakes of all nutrients and total energy intake may be determined. Total energy intake is critical in nutritional epidemiology for energy adjustment and for assessment of misreporting.

Criticism of use of FFQs to assess diet-disease relationships

There is debate about the relative merits of using FFQs in large-scale prospective studies and whether FFQs are sensitive enough to detect important diet-disease relationships [8-10].

Results from studies using biomarkers of specific nutrients as the reference method for assessment of dietary intake suggest that the measurement error associated with FFQs is larger than was previously estimated [11,12]. Others have found that the FFQ performs well in comparison with diet records [4]. It is important to remember that not all FFQs are the same and some may be better than others in terms of assessing food and nutrient intakes. For any study, the advantages and disadvantages of using FFQs compared to other dietary assessment methods should be carefully considered [13].

- Responses about frequencies of dietary consumption can be analysed in their raw state.

- Participants can be ranked into broad categories of intakes of specific foods and food components or of nutrient intake.

- Nutrient intakes can be calculated based on the product of their reported frequency of consumption, their reported or pre-specified portion size per serving, and the nutrient contents of each food item. Typically, each FFQ is linked to a specific in-house food composition table where FFQ’s items are matched with items in a food composition table.

- As responses to FFQs are standardised, data can be entered and analysed in a comparatively short period of time, often in an automated process, allowing dietary data of a large number of people to be collected relatively inexpensively. There is also less need for nutritional expertise in data entry, though for incorporation of additional foods and interpretation of results, nutritional researchers are strongly recommended.

Key characteristics of food frequency questionnaires are described in Table D.10.2.

Strengths

- Low respondent burden - typically takes 10-20 minutes to complete

- Comparatively easy and flexible to administer

- Low cost compared to other dietary assessment methods

- Useful to repeat dietary assessment over years

- More complete data may be collected if the FFQ is interviewer-administered but respondent bias may be less if self-administered

- The standardisation of responses enables FFQs to be analysed relatively quickly and in some cases in an automated fashion

- Existing FFQs can be modified for use in new studies if the analysis package is available

- Designed to capture habitual diet and foods not consumed on a regular basis

Limitations

- A comprehensive list of all foods eaten cannot be included and reported intake is limited to the foods contained in the food list

- Accurate reporting relies on the respondent's memory

- Bias may be introduced with respondents reporting eating ‘good’ foods more frequently (over-estimation) or the consumption of ‘bad’ foods less often (under-estimation). There is some evidence that over-estimation increases with the length of the food list

- A relatively high degree of literacy and numeracy skills are required if self-administered, although less than for other methods; interviewers can help overcome this problem

- Estimating portion sizes may be difficult and the use of small, medium, and large to describe portion size may not have a commonly accepted meaning

- FFQs are population-specific and considered to be inappropriate for use in different populations unless dietary habits are confirmed to be very similar

- The food list may not be reflective of the dietary patterns of the population to be studied; ethnic differences in a population may not be captured for example

- Pre-prepared meals such as ready meals or take-away foods may not be easy for respondents to classify if the food list is based on more basic food categories

Table D.10.2 Characteristics of food frequency questionnaires.

| Consideration | Comment |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | Any |

| Cost of development | Medium |

| Cost of use | Low |

| Participant burden | Low |

| Researcher burden of data collection | Low |

| Researcher burden of coding and data analysis | Medium |

| Risk of reactivity bias | No |

| Risk of recall bias | Yes |

| Risk of social desirability bias | Yes |

| Risk of observer bias | No |

| Participant literacy required | Maybe |

| Suitable for use in free living | Yes |

| Requires individual portion size estimation | Maybe |

Considerations relating to the use of FFQs for assessing diet in specific populations are described in Table D.10.3.

Table D.10.3 Dietary assessment by food frequency questionnaire in different populations.

| Population | Comment |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy | Suitable. |

| Infancy and lactation | Requires proxy. |

| Toddlers and young children | May require proxy or adult assistance. |

| Adolescents | Suitable. |

| Adults | Suitable. |

| Older adults | May require proxy depending on cognitive function [14]. |

| Ethnic groups | Suitable, if developed for the purpose. |

- Interviewer-administered FFQs will help ensure that questionnaires are fully completed and should help reduce any ambiguity respondents have with specific questions. Face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews can be carried out. Interview by phone or the internet can be less costly than in-person interviews and have the advantage of being able to reach a large number of people in different geographic regions.

- It is time-consuming and tedious to answer long lists of questions in the FFQ format if it is being interviewer-administered, requiring full concentration to the end. Appropriate ways of asking the questions and recording responses need to be considered, not just reading out the questionnaire.

- For a long-term prospective cohort or serial surveys over years, the same FFQ can be used repeatedly. However, temporal changes in dietary environments and trends in a given population would occur if the duration is long. Proper adjustment or a new study to assess the validity is ideal to implement.

- Paper-based FFQs can be designed to be scanned by which data entry is facilitated and less likely to involve errors.

- If the portion size is to be queried, its reporting can be improved with picture booklets or other portion size estimation aids provided to respondents.

- Trained interviewers (if the FFQ is interviewer-administered).

- Trained diet coders.

- Nutrient database and analysis program (for estimation of nutrient intake).

- Portion estimation aids.

- Standardised operating procedures - for data checking, cleaning, and analysis.

A method specific instrument library is being developed for this section. In the meantime, please refer to the overall instrument library page by clicking here to open in a new page.

Adaptation of an existing questionnaire

The development of a new FFQ is costly in terms of time and resources and therefore the use of an existing questionnaire might be appealing. However, several points should be considered before selecting an existing questionnaire for use in a study. These include:

- Do the original objectives of the questionnaire meet the requirements of the new study?

- Who were the original target population and how does this compare with the new target population?

- Has the questionnaire been validated/calibrated and if so, in which population group and how, i.e. which comparison method was used and which time frame was chosen?

- Is the expertise to modify the analysis package available?

Developing or adapting a food list

It is important to consider carefully the level of grouping of foods. The aggregation of some foods with dissimilar eating patterns (e.g. tomatoes and tomato juice) can make it cognitively difficult for respondents to report frequency of consumption and may lead to an underestimation of intake.

For some food items, asking questions about single items can help respondents differentiate between similar foods with different nutritional profiles (e.g. full fat milk, semi-skimmed milk etc).

In order to achieve a balance between approximation of the absolute intake and burden for the participants, the following steps can be taken:

- Derive an extensive food list of the food items containing the nutrients of interest in a given population or for a specific research question.

- Use open-ended data (e.g. from 24-hour recalls or weighed food records) to identify foods commonly consumed and thus important sources of absolute intakes.

- Identify major foods contributing to specific nutrients or dietary habits using a statistical approach (e.g. stepwise regression) in a pilot study or a survey [15].

There may be situations in which the purpose of the FFQ is very specific and a shortened food list is preferable such as the assessment of intakes of calcium and other nutrients potentially involved in bone health, but this limits the use of the questionnaire and the data derived to that use only.

- Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology: Oxford University Press, USA; 1998.

- Willett WC. Invited commentary: comparison of food frequency questionnaires. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(12):1157-9; discussion 62-5.

- Cade JE, Burley VJ, Warm DL, Thompson RL, Margetts BM. Food-frequency questionnaires: a review of their design, validation and utilisation. Nutr Res Rev. 2004;17(1):5-22.

- Brunner E, Stallone D, Juneja M, Bingham S, Marmot M. Dietary assessment in Whitehall II: comparison of 7 d diet diary and food-frequency questionnaire and validity against biomarkers. Br J Nutr. 2001;86(3):405-14.

- Mosdol A, Witte DR, Frost G, Marmot MG, Brunner EJ. Dietary glycemic index and glycemic load are associated with high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol at baseline but not with increased risk of diabetes in the Whitehall II study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(4):988-94.

- Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, Ferrari P, Norat T, Fahey M, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6b):1113-24.

- Greenwood DC, Cade JE, Draper A, Barrett JH, Calvert C, Greenhalgh A. Seven unique food consumption patterns identified among women in the UK Women's Cohort Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(4):314-20.

- Bingham SA, Day N. Commentary: fat and breast cancer: time to re-evaluate both methods and results? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):1022-4.

- Freedman LS, Potischman N, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Schatzkin A, Thompson FE, et al. A comparison of two dietary instruments for evaluating the fat-breast cancer relationship. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):1011-21.

- Kristal AR, Peters U, Potter JD. Is it time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(12):2826-8.

- Day N, McKeown N, Wong M, Welch A, Bingham S. Epidemiological assessment of diet: a comparison of a 7-day diary with a food frequency questionnaire using urinary markers of nitrogen, potassium and sodium. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(2):309-17.

- Molag ML, de Vries JH, Ocke MC, Dagnelie PC, van den Brandt PA, Jansen MC, et al. Design characteristics of food frequency questionnaires in relation to their validity. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(12):1468-78.

- McNeill G, Masson L, Macdonald H, Haggarty P, Macdiarmid J, Craig L, et al. Food frequency questionnaires vs diet diaries. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):884; author reply 5.

- Arsenault LN, Matthan N, Scott TM, Dallal G, Lichtenstein AH, Folstein MF, Rosenberg I, Tucker KL, Validity of Estimated Dietary Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid Intakes Determined by Interviewer-Administered Food Frequency Questionnaire Among Older Adults With Mild-to-Moderate Cognitive Impairment or Dementia. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(1):95-103.

- Freedman LS, Potischman N, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Schatzkin A, Thompson FE, et al. A comparison of two dietary instruments for evaluating the fat-breast cancer relationship. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):1011-21.