Introduction

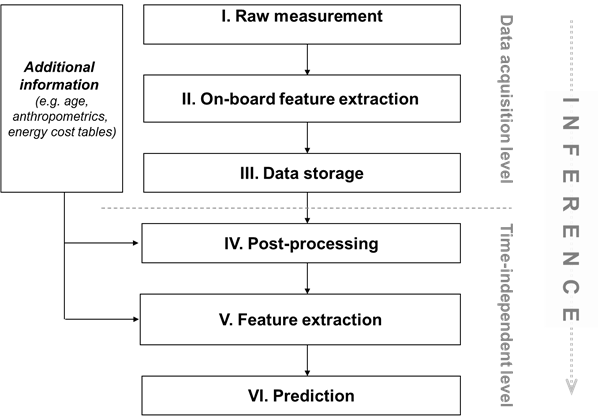

Estimates of diet, physical activity, or anthropometry should be as close to the true value as possible. The process of estimating this true value involves several stages of inference. Errors can be introduced at each of these stages, weakening the inference and resulting in estimated values which do not fully represent the true values. An example of these stages of inference is shown in Figure C.1.1, which is split into two levels:

The data acquisition level, which can be further divided into:

- Raw measurement

- On-board feature extraction – initial filtering or transformation of information (e.g. the brain filtering out unimportant sensory information or transformation of raw acceleration into physical activity counts)

- Data storage

The time-independent level, which can be further divided into:

- Post-processing – removal of invalid data, dealing with outliers, etc.

- Feature extraction – intermediary summary variables derived from the data in order to aid prediction (in some cases, extracted features are the final estimates)

- Prediction – the final estimate of the true value of the behaviour or characteristic of interest, which would be reported in research output

Figure C.1.1 Stages of inference involved in predicting the true value by measurement using the tool and overall method. Adapted from [ 2 ].

Tools

A tool, sometimes an ‘instrument’, refers to the mechanism by which data are initially acquired in the data acquisition phase (see Figure C.1.1 above). Tools produce measurements.

There are often different tools which fall under the same category, for example, there are different examples of a food frequency questionnaire, such as the Harvard or Willett questionnaire [3] and the Block questionnaire [1]. Similarly, there are variations in the technical specifications of different accelerometer models used to measure physical activity.

Methods

The term ‘method’ is used to describe the combination of the tools employed at the data acquisition level, and how the measurements are used to derive estimates during the time-independent level.

Measurements vs. estimates

A tool produces a measurement (e.g. the number of servings of fruit per day), whereas a given method provides an estimate of a target variable of interest (e.g. vitamin C intake) through a series of inferential steps. In some circumstances, the measurement is used in its raw form (e.g. height measurement), and the estimate and measurement are the same.

The manner in which measurements by tools are used to derive estimates of the target variable of interest varies by study and sometimes within a study. A single tool can consequently be a component of multiple different methods that produce different target variables.

Additional information as components of methods

Additional information, not captured by the tool itself, can also form a part of the overall method. This can include:

- Participant information such as age, sex, height, and weight

- Energy cost tables for use in conjunction with physical activity questionnaires

- Nutritional databases for use in conjunction with weighed food diaries

- Standardised tables for height and weight used to determine growth compared to the general population

Tools vs. brands

Some tools are developed by companies and assigned brand and/or model names. For example, there are many different brands of accelerometers for measuring physical activity, and each of these brands might have various models with different features. Similarly, some anthropometric tools are branded (e.g. Seca), as are some dietary analysis software products.

- Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(3):453-69.

- Corder K, Ekelund U, Steele RM, Wareham NJ, Brage S. Assessment of physical activity in youth. J Appl Physiol 2008;105(3):977-87.

- Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(1):51-65.