- Nutrients, foods, and diets

- Dietary adequacy and nutritional requirements

- Diet variation, quantification, and misreporting

- Food composition data and databases

- Data processing

- Introduction to subjective measures

- Estimated food diaries

- Weighed food diaries

- 24-hour dietary recalls

- Food frequency questionnaires

- Diet checklists

- Diet histories

- Technology-assisted dietary assessment

Diet checklists

The following outcomes can be assessed using a dietary checklist:

- Frequency, amount, or other attributes of dietary consumption in a brief list of dietary items, including foods, food groups, and supplements

- Adherence to a certain dietary intervention or a special dietary pattern

- Likelihood of being exposed to food pathogens

- Dietary habits or consumption of specific foods not likely to be captured in other methods

- Group-level dietary consumption or exposure

A checklist that is designed for a specific purpose tends to be less detailed in contrast to other methods. The outcomes measured by a dietary checklist depend upon the design. Any outcomes can be assessed if targeted as indicated in Table D.11.1. For example:

- In a clinical setting pertaining to anaemia, a checklist capturing major food sources and supplements of iron and vitamin B12 may be sufficient and allow calculation of the amount of the specific nutrients

- In research on the effect of providing breakfast to those who tend to skip breakfast on health outcomes, a checklist to assess adherence to the intervention and related habits may be sufficient

- In research on foodborne illness, a checklist can be about food consumption on a very specific occasion (e.g. “the wedding ceremony at Hotel X on 22 August 2015”)

A checklist can be used for an assessment of group-level exposure to certain foods in a certain environment. For example:

- Vending machines for snacks, soft drinks, or plain water in a school

- Types of foods sold in a restaurant or deli, such as raw meats, and foods that can cause allergic reactions

- Marketing policy and practice of a local supermarket or stores in a school

Table D.11.1 Dietary outcomes assessed by dietary checklist.

| Dietary dimension | Possible to assess?* |

|---|---|

| Energy and nutrient intake of total diet | No |

| Intake of specific nutrients or food | Yes |

| Infrequently consumed foods | Yes |

| Dietary pattern | Yes |

| Habitual diet | Yes |

| Within-individual comparison | Yes |

| Between-individual comparison | Yes |

| Meal composition | Yes |

| Frequency of eating/meal occasions | Yes |

| Eating environment | Yes |

| Adult report of diet at younger age | Yes |

* all are possible, except for the first one, but dependent on how a checklist is developed, and whether it is implemented with or without repeats.

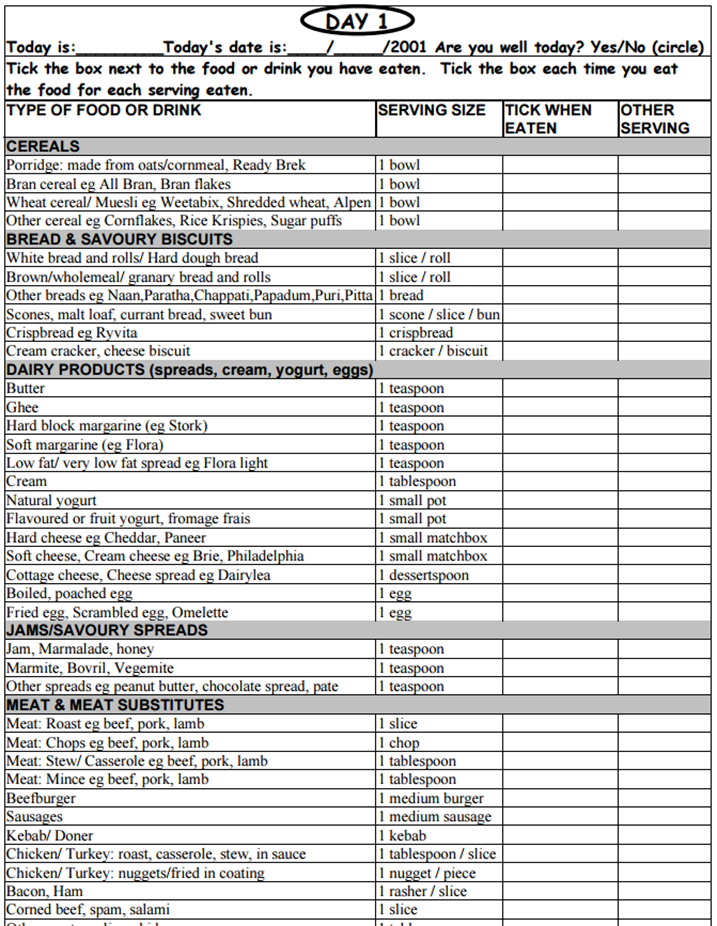

A dietary checklist can be either self-administered or interviewer-administered. A dietary checklist includes elements of a food frequency questionnaire (as it is based on a pre-printed food list). Respondents examine a list of foods, supplements, or other dietary items and cross-tabulate with attributes such as specified serving size (e.g. slices, teaspoons) and frequency of consumption, or both, ticking the boxes appropriately. An example of a dietary checklist is displayed in Figure D.11.1.

An assessor can administer a checklist to a respondent through face-to-face or phone interview. Alternatively, it may be preferable or required to send a checklist to a respondent through post or email and request him/her to complete it and send it back.

Use of blank space for each item and for an entire list is helpful to encourage a respondent to provide any information such as specific dietary patterns (e.g. vegan, a habit related to a religion, being on a weight-loss diet), alternative serving sizes for certain foods, and his/her key foods not listed. Sub-sections for a specific setting, e.g. ‘eating out and takeaway’ section, may help, depending on the aims of a checklist.

Figure D.11.1 Example of dietary checklist from the Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey study. Note that this is one of five pages completed per day.

Source: [10].

Screening individuals for a specific dietary problem or intervention, for example:

- to assess adherence to specific dietary patterns, for example, the Mediterranean diet [2,3].

- to identify the need for education about unusual dieting.

- to identify dietary behaviours or experiences associated with food poisoning, allergy, or dieting.

- to implement a targeted intervention to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.

- to identify the need to encourage dietary consumption with family members.

- to assess adherence to an intervention.

Categorical or continuous answers to each item, such as

- Yes or No for consumption of certain foods, preference of foods or related behaviours, experiences of having meals in a dietary setting (e.g. a specific restaurant).

- Frequency of consumption or a dietary practice over a certain period of time (e.g. frequency of snacking).

Answers can be combined for the purpose of a checklist

- to estimate consumption of a food group.

- to assess an overall degree of adherence to a certain intervention.

- to estimate nutrient intakes from selected food items and supplements.

Strengths

- Flexible to design a checklist and assess a targeted dietary habit or consumption. For instance, dietary assessment for foodborne illness often has a checklist to reflect this strength, to assess dietary exposure on a very specific occasion [4].

- Low participant burden. For example, in the Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey (LIDMS), respondents preferred the food checklist over a 24-hour recall and weighed food diary [5].

Limitations

- Not useful to capture detailed dietary habits, or to answer many different clinical or epidemiological questions

- A risk of systematic errors, which may result in recall bias, depending on the study design

- A respondent may need to be literate, numerate, or both, depending on the study design. The LIDMS (Figure D.2.6) identified that the following requirements had been the most common issues: ticking the boxes (18%), understanding the portion sizes (18%), understanding what was required (16%), understanding a listed food consumed in a unique population only (15%), recording food eaten outside the home (15%) [5].

Table D.11.2 Characteristics of dietary checklists.

| Consideration | Comment |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | Any |

| Cost of development | Low |

| Cost of use | Low |

| Participant burden | Low |

| Researcher burden of data collection | Low |

| Researcher burden of coding and data analysis | Low |

| Risk of reactivity bias | Yes |

| Risk of recall bias | Yes |

| Risk of social desirability bias | Yes |

| Risk of observer bias | Yes |

| Participant literacy required | Depends on whether interviewing or not |

| Suitable for use in free living | Yes |

| Requires individual portion size estimation | Depends on design |

Considerations relating to the use of dietary checklists for assessing diet in specific populations are described in Table D.11.3.

Table D.11.3 Suitability of dietary checklists in different populations.

| Population | Comment |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy | Suitable |

| Infancy and lactation | Requires proxy |

| Toddlers and young children | May require proxy or adult assistance |

| Adolescents | Suitable |

| Adults | Suitable |

| Older Adults | May require proxy depending on cognitive function |

| Ethnic groups | Suitable, if developed for the purpose |

- Trained fieldworkers can probe for missing items or any issues during and at the end of the implementation.

- The food list must be designed for a specific purpose of research.

- Trained fieldworkers to instruct respondents on how to complete the dietary checklist, monitor completion, and review the outputs at the end of the assessment

- Depending on the study design and aims, the following items may also be required:

- Additional questionnaire to aid interpretation.

- Instructions on completion and return of the checklist.

- Trained diet coders.

- Nutrient database and analysis program.

A method specific instrument library is being developed for this section. In the meantime, please refer to the overall instrument library page by clicking here to open in a new page.

As a checklist can be flexible and tailored for a specific research aim, developing a checklist is often the last step in designing a study after all variables of interest have been identified. As a general rule in a questionnaire method, the following attributes should be confirmed:

- Simplicity/clarity

- Relevance to research aims

- Completeness to assess target variables

Points to consider when drafting questions (adapted from [4]):

- Clarify the aim of a checklist

- Keep wording informal, conversational, and simple

- Avoid jargon and sophisticated language

- Avoid long questions (but vary question length)

- Keep questions appropriate to the educational, social, and cultural background of respondents

- Avoid leading questions linked to social or personal desirability

- Avoid negative questions, questions beginning with “Why”, hypothetical questions

- Limit each question to a single subject

- Pay attention to sensitive issues

- Check the adequacy of the list of possible responses to close-ended questions, and the need for open-ended questions

Whenever available and appropriate, the development needs to account for outcomes from dietary studies previously conducted in the same or similar populations. In the phase of finalising a checklist, a mock implementation is essential to confirm a time to complete and ease of completing the checklist.

- Nelson M DK, Holmes B, Thomas R & Dowler E. Low Income Diet Methods Study: Project for Food Standards Agency. London: 2003.

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fernandez-Jarne E, Serrano-Martinez M, Wright M, Gomez-Gracia E. Development of a short dietary intake questionnaire for the quantitative estimation of adherence to a cardioprotective Mediterranean diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(11):1550-2.

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Garcia-Arellano A, Toledo E, Salas-Salvado J, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43134.

- World Health Organisation. Foodborne disease outbreaks: Guidelines for investigation and control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2008.

- Holmes B, Dick K, Nelson M. A comparison of four dietary assessment methods in materially deprived households in England. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(5):444-56.