- What is physical activity?

- Energy expenditure

- Movement

- Posture

- Volume, intensity, duration, frequency

- Physical behaviour type

- Contextual information: Domain, spatial settings and social contexts

- Sedentary behaviour

- Physical activity guidelines

- Physical activity variation

- Inventory and taxonomy of pattern metrics

- Introduction to objective methods

- Pedometers

- Accelerometers

- Heart rate monitors

- Combined heart rate and motion sensors

- Direct observation

- Doubly labelled water

- GPS and other GNSS receivers

- Multi sensor monitors

- Harmonisation of physical activity data

- Case study: Physical activity during pregnancy and anthropometry of the offspring

- Comparison of three harmonisation methods using validation data

- Network harmonisation of physical activity data using validation data

- Physical Activity Assessment Video Resources

- Getting participants started with the Axivity Monitor

- Wearing the Axivity Monitor

- Getting participants started with the ActiGraph Monitor

- Getting participants started with the Actiheart Monitor

- Wearing the ActiGraph monitor

- Step Test Procedure

Diaries and logs

Diaries and logs typically allow detailed descriptions of duration, intensity, type and context of physical activity. Diaries in particular use free-form data capture resulting in rich descriptive information from the participant. Depending on the design of the diary or log, it is possible to capture details of any dimension of physical activity provided it is completed accurately, as described in Table P.2.5.

Table P.2.5 The dimensions which can be assessed by physical activity diary/log.

| Dimension | Possible to assess? |

|---|---|

| Duration | ✔ |

| Intensity | ✔ |

| Frequency | ✔ |

| Volume | ✔ |

| Total physical activity energy expenditure | ✔ |

| Type | ✔ |

| Timing of bouts of activity | ✔ |

| Domain | ✔ |

| Contextual information (e.g. location) | ✔ |

| Posture | ✔ |

| Sedentary behaviour | ✔ |

A diary or log is completed as bouts of physical activity occur, or at regular time intervals throughout the day. In contrast, physical activity questionnaires are completed retrospectively. Due to participant burden, the time frame is rarely longer than 7 days. The time frame should ideally be long enough to account for any real between-day variability in the outcome of interest. Some research has indicated that up to two weeks of diary data are necessary to provide a reliable estimate of habitual physical activity (Baranowski & de Moor, 2000).

Logs and diaries can be completed in both paper-pencil and electronic formats, while the availability of portable electronic devices has seen the development of new techniques to collect ‘real-time’ physical activity data.

The terms diary and log are sometimes used interchangeably, however there are key differences between the two methods, and different ways of administering them.

Diaries

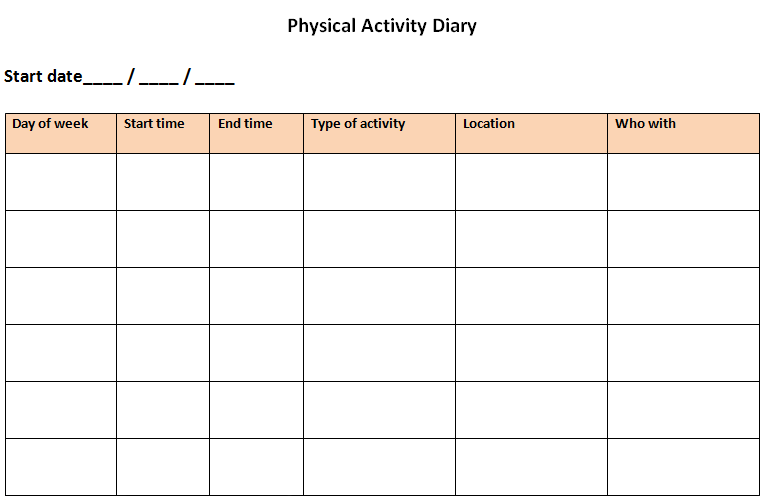

Diaries use a free-form style of data entry by participant, normally in table format organised by day and/or time periods (morning, afternoon, evening etc.), as shown in Figure P.2.2. Participants provide separate detail-rich descriptions for each bout of activity. Dimensions in each diary vary, but can include:

- Date or day of week

- Start and end time of activity or duration

- Type

- Intensity

- Context – e.g. location, purpose or other participants

Figure P.2.2 Example of a physical activity diary.

Logs

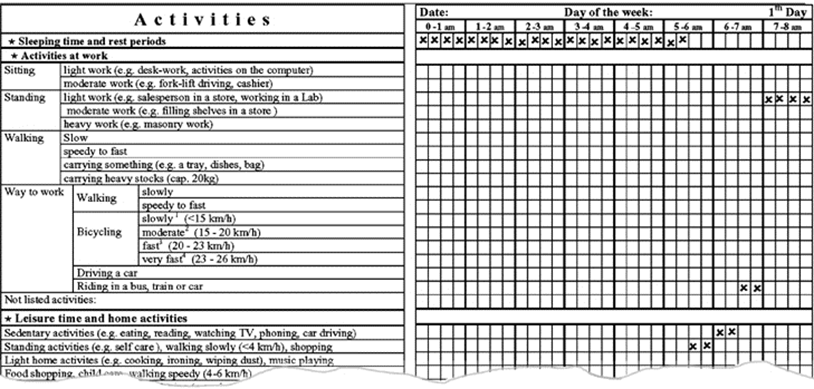

Logs require more structured reporting by participant. Days are broken into shorter segments, such as 96 * 15 minutes. Each segment is then assigned a code from a list, or cross-tabulated with columns/rows representing dimensions of activity such as: (see Figure P.2.3).

- Type

- Context

- Intensity

- Posture

The choice of segment length for log is important. Completing diaries and logs every 15 minutes may lead to the omission of some activities, but reducing the period may be too intensive and lead to non-completion.

The scope of the data recorded is constrained by the design of the log; there may be only certain types, contexts or intensities included. Similarly, the temporal resolution is limited to the segment duration, i.e. activities are only recorded with 15 minute accuracy.

Figure P.2.3 Example of a log method which uses cross-tabulation to describe daily activity in 15 minute segments. Source: Koebnick et al., 1998.

Benefits of electronic vs. paper-pencil

- Greater flexibility e.g. by adding explanatory messages, error corrections and prompts

- Immediate data entry, avoiding coding errors

- Possibility of direct scoring, reporting and interpreting of results

- Reduction of research time and cost

- Potentially greater motivation among participants

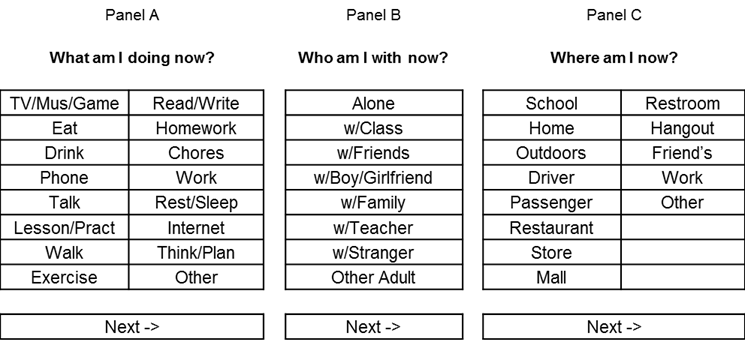

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA)

EMA (Dunton et al., 2005) is a prompting method which instructs participants to report their current activity in real-time; no recall is required. EMA records not just the type of activity but also simultaneous capture of contextual variables.

Requests for information are sent via electronic device (e.g. mobile phone):

- At regular intervals

- At random

- By change in activity intensity detected by a monitor

This tool may underestimate physical activity as it is difficult to respond to prompts at higher intensities. In addition, the procedures and demands of EMA may introduce sampling bias. Similar to conventional activity logs, the resolution of duration data is determined by the frequency of prompts, and it may be difficult to measure time spent in different activity types and contexts, especially if prompts are sent at random.

Figure P.2.4 Example of stages of input during Ecological Momentary Assessment. Source: Dunton et al., 2007.

Proxy reports

Proxy methods refer to the implementation of diary or log methods in scenarios where the respondent is not the individual being assessed. The choice of proxy-reporter may be vital to the accuracy of the reports, and normally made on the basis of intimate knowledge of the individual, proximity, or their professional capacity.

Recording physical activity diary or log is a complex task, which may be particularly difficult for some populations, such as: young children, adults with cognitive impairment, chronically ill, disabled. Individuals may lack the cognitive ability to record the intensity, frequency and particularly the duration of activities. Alternatively, they may not interpret items as intended (especially those with complicated designs), or fully understand the meaning of abstract terms such as “moderate to vigorous physical activity”.

Based on issues of equity, inclusivity, sample size, missing data and bias, use of proxies may be preferable to excluding or not investigating individuals and populations who cannot self-report. Proxy methods also provide some degree of objectivity of estimates of physical activity – individuals do not report their own activity and should have no control over what is recorded.

Use of a proxy-reporter has limitations, such as:

- Level of observation of the individual’s activity by the proxy-reporter – this is difficult for habitual activity over a number of days, weeks or years, and some domains of activity may be inaccessible.

- Estimation of activity intensity for another individual is particularly difficult, especially when there are differences in age, sex, body mass or degree of disability between subject and proxy-reporter

- Social desirability bias such as in the case of teachers, parents and care workers, all of whom may have cause to present a more desirable account of the individual’s physical activity

- Reports may be influenced by the proxy-reporter’s characteristics or subjective experiences of their own physical activity

- Potential heterogeneity of proxy-reporters (e.g., spouse, trainer, coach, parent, caregiver) within studies

- It may be difficult to compare proxy-reports from different reporters or with subjective reports

Diary and log methods are useful for studies that require more detailed descriptions of duration, intensity, type and context of physical activity. They can be used to:

- Describe temporal patterns of the intensity, type and context of physical activity throughout the day

- Quantify changes in physical activity during an intervention study

- Assess the prevalence of major physical activity outcomes (e.g. adherence to guidelines on moderate-to-vigorous physical activity)

- Examine dose-response associations of specific behaviours with health outcomes

- Provide qualitative information to complement physical activity data which has been recorded objectively

The physical activity estimates derived tend to be of greater temporal resolution than from questionnaires. These are dependent upon the detail provided by participants and/or included in the log by the researcher, but can include:

- Temporal changes of the intensity of physical activity

- Duration and timing of physical activity occurring at different intensities (e.g. MVPA), of different types (e.g. cycling), or in different contexts (e.g. minutes of occupational activity)

- Total physical activity energy expenditure at group level (sometimes expressed as MET hours per day or week)

Interpretation of data from a dairy/log is aided by additional information, such as:

- Demographic data (e.g. age, sex)

- Anthropometric data (e.g. body mass)

- Energy cost tables

- Assumptions about activity levels (e.g. that a manual labourer is more active than an office worker)

It is usual for MET values to be assigned based on the intensity or type data reported by the participant. These MET intensity scores are used alongside the reported duration and frequency to derive the volume of activity. Research assistants who will be assigning MET values to diary data should be trained and assessed first to ensure inter-rater agreement and high objectivity. Since timing of activity is recorded, they can also be used to describe change in energy expenditure over 24 hours, or patterns over a number of days.

This approach assumes the following:

- MET values recorded during calibration studies are generalisable to the sample of the current investigation

- MET values of activities do not vary within and between individuals

- Physical activity intensity is uniform during activities

- Durations of activity reported represent the actual time for which the activity was conducted, for example, 1 hour swim session may include changing and showering time

The extraction of features such as MET-hours in different types or domains is an intermediary step, these features can then combined to estimate final target variable(s), or be used in their current state. Outcomes extracted from diaries and logs may be averaged across multiple days of measurement to estimate a ‘typical’ day’s activity.

Characteristics of diary/log methods are described in Table P.2.6.

Strengths

- Diaries and logs provide detailed and comprehensive information about the physical activity undertaken

- Because the time of activity is recorded, can be time-matched to other data, e.g. accelerometer, GPS receiver, heart rate monitor

Limitations

- Diaries are more detailed but more burdensome for individuals to complete than logs, and the data are more complex to reduce and enter to dataset

- The level of compliance required makes the method unsuitable for younger children (under 10 years)

- Respondents may not comply with instructions to complete the diary or log prospectively

Table P.2.6 Characteristics of diary and log methods.

| Consideration | Comment |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | Small to large |

| Relative cost | Low |

| Participant burden | High |

| Researcher burden of data collection | Low |

| Researcher burden of data analysis | High if completed manually |

| Risk of reactivity bias | Yes |

| Risk of recall bias | Minimised if completed at time of consumption |

| Risk of social desirability bias | Yes |

| Risk of observer bias | No |

| Participant literacy required | Yes |

| Cognitively demanding | Yes |

- The population of interest determines the choice of diary/log. Different populations show different activity types, contexts and patterns and may require different energy cost tables, administration modes, different languages etc.

- If using a pre-defined list of activities ensure the activities are appropriate to the population being studied, as activities are likely culturally dependent (activity types, language, etc.)

- The method should be been examined in terms of reliability and validity in a population similar to the one to be examined

- The suitability of diaries/logs for assessing physical activity is summarised by population in Table P.2.7

Table P.2.7 Physical activity assessment by diaries/logs in different populations.

| Population | Comment |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy | |

| Infancy and lactation | Requires proxy. |

| Toddlers and young children | Requires proxy. |

| Adolescents | Requires proxy to save duplicate portions and if necessary record diary. |

| Adults | |

| Older Adults | May require proxy depending on cognitive function. |

| Ethnic groups | May require language/cultural specificity. If translating a diary/log, translation and back translation is good practice. |

| Other |

- To enhance compliance it may be useful to prompt individuals by phone, email or SMS

- Clear instructions (ideally face-to-face) must be provided, particularly if prospective recording of activity is required

- The diary or log should be well formatted and easy to complete, and of small size if this has to be carried around during the day

- Since the time-frame is relatively short (normally no more than seven days), this method may be subject to seasonal biases

- Activity diary or log - to date these have been mainly paper based

- Portable electronic device for ecological momentary assessment

- Research assistant(s) to administer and provide encouragement during the measurement period

- Clear written instructions on completion and return of the tool

- Database to process the data

- Activity cost table such as compendium of physical activities

- Demographic information

A list of specific diary and log instruments is being developed for this section. In the meantime, please refer to the overall instrument library page by clicking here to open in a new page.

If a new diary/log is to be developed:

- Can existing valid diaries or logs be adapted and/or combined?

- Adapt format and layout to population (e.g. larger font and tracking lines for elderly); ensure clarity and structure; give precise instructions; request information in precise manner, one piece of information at a time; separate days into segments

- Pilot testing for refinement of diary/log, which aids with choice and order of activities, response categories, etc.

- Is choice of criterion optimal when examining validity? Not all criterion measures are equally appropriate as criterion for the different dimensions derived from a diary/log

- Allow for additional socio-demographic questions

- Diary or log must be valid for the population under study, which may be difficult for population groups which are studied less frequently

- Modified diaries or logs require testing of validity and reliability

For proxy methods, it is not advisable to simply translate a self-report instrument to proxy-report without testing. A suitable proxy-report method must therefore:

- Be appropriate for the dimensions, purpose, context and population in the same way a self-report method should

- Be valid and reliable when used via a proxy-reporter; this requires careful consideration and testing – methods which are suitable for use in self-report may not be appropriate or feasible by proxy

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger RS. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1993;25:71-80

- Ainsworth BE, Bassett DR, Strath SJ, Swartz AM, O'Brien WL, Thompson RW, Jones DA, Macera CA, Kimsey CD. Comparison of three methods for measuring the time spent in physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32:S457-64

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O'Brien WL, Bassett DR, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32:S498-504

- Baranowski T, de Moor C. How Many Days Was That? Intra-individual Variability and Physical Activity Assessment. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2015;71 Suppl 2:74-8

- Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Leblanc C, Lortie G, Savard R, Thériault G. A method to assess energy expenditure in children and adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1983;37:461-7

- Bratteby LE, Sandhagen B, Fan H, Samuelson G. A 7-day activity diary for assessment of daily energy expenditure validated by the doubly labelled water method in adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;51:585-91

- Dunton GF, Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Henker B, Floro JN. Using ecologic momentary assessment to measure physical activity during adolescence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:281-7

- Dunton GF, Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Floro JN. Mapping the social and physical contexts of physical activity across adolescence using ecological momentary assessment. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34:144-53

- Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sjöström M. Total daily energy expenditure and patterns of physical activity in adolescents assessed by two different methods. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 1999;9:257-64

- Freedson PS, Evenson S. Familial aggregation in physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1991;62:384-9

- Garcia AW, Pender NJ, Antonakos CL, Ronis DL. Changes in physical activity beliefs and behaviors of boys and girls across the transition to junior high school. The Journal of Adolescent Health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 1998;22:394-402

- Irwin ML, Ainsworth BE, Conway JM. Estimation of energy expenditure from physical activity measures: determinants of accuracy. Obesity Research. 2001;9:517-25

- Koebnick C, Wagner K, Thielecke F, Moeseneder J, Hoehne A, Franke A, Meyer H, Garcia AL, Trippo U, Zunft HJ, et al. Validation of a simplified physical activity record by doubly labeled water technique. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:302-9

- Mâsse LC, Heesch KC, Fulton JE, Watson KB. Raters' Objectivity in Using the Compendium of Physical Activities to Code Physical Activity Diaries. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science. 2002;6(4):207-24.

- Matthews CE. Use of self report instruments to assess physical activity. In: Welk GJ, editor. Physical Activity Assessments for Health-Related Research. Champaigne, IL: Human Kinetics; 2002. p. 107-24.

- Oliver M, Schofield GM, Kolt GS. Physical activity in preschoolers: understanding prevalence and measurement issues. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2007;37:1045-70

- Ridley K, Ainsworth BE, Olds TS. Development of a compendium of energy expenditures for youth. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5:45

- Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2015;71 Suppl 2:1-14

- Schmidt MD, Freedson PS, Chasan-Taber L. Estimating physical activity using the CSA accelerometer and a physical activity log. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003;35:1605-11

- Timperio A, Salmon J, Rosenberg M, Bull FC. Do logbooks influence recall of physical activity in validation studies? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36:1181-6

- Tulve NS, Jones PA, McCurdy T, Croghan CW. A pilot study using an accelerometer to evaluate a caregiver's interpretation of an infant or toddler's activity level as recorded in a time activity diary. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2007;78:375-83